Visualizing Confinement

In July 2021, Pioneer Works presented Coby Kennedy’s Kalief Browder: The Box, an eight-by-ten-by-six-feet sculpture that replicates the exact dimensions of a solitary confinement cell. Framed by steel and lit from below, the plexiglas enclosure pays tribute to Kalief Browder, who at seventeen-years-old was arrested for a robbery he did not commit. Imprisoned without trial on Rikers Island for three years, the teenager was forcibly subjected to a solitary confinement cell for torturously long segments, totalling over 700 days, that caused lasting psychological trauma, resulting in suicide two years after his eventual release. Through creating this work, Kennedy hopes to shed light on the struggle that Browder and his family endured—and the resilience they displayed—and to incite meaningful contemplation on the devastating phenomenon of solitary confinement, and mass incarceration at large.

For Broadcast, Kennedy converses with activist, scholar and founding director of UCLA Prison Education Program Bryonn Bain; production agency Negative Space founder Sam Giarratani; and artist and For Freedoms founder Hank Willis Thomas. Together, they expand on the behind-the-scenes production of Kalief Browder: The Box, and reflect on the intersections between art and activism.

So Coby, do you want to tell that story?

Yeah. Preparing this project has been wild, because I was injured early on when 1,500 pounds of tempered glass fell on me. Biblically long story short, I was behind an A-frame and these eight-by-eight-feet panels just came down on me. There were about four or five of them, and I braced it with a few other people who were all trying to hold it up. All the pressure just went straight into my knee, and ripped my ligament off my kneecap. The glass shattered, and massive chunks came down on my shin. Getting the show ready—such a large sculpture—was an uphill battle, but Pioneer Works really jumped in. And I've been glad working with them, because they shared the focus and the vision.

They say artists don't put their bodies on the line for the work. For the movement, you know what I'm saying? A man put his body on the line for it. That's what's up, much respect.

You know, people always say, “They put blood, sweat, and tears into the work.” I literally put my blood in, but I'm glad everything worked out the way that it did with the project.

Let’s introduce ourselves, and each speak about how we describe our work as artists. I know you are all Pisces, so we’re going to flow like water.

I'm as Piscean as they come. Ever since I was a kid, I could feel what other people are feeling and, ever since my first interaction with Kalief's story, I've always felt it almost personally. It dug into a lot of my core fears, of losing my own agency. The project is my attempt to have people understand what’s going on in a country where many would think something like this can never happen.

It's happening every day. Can you share the quote that inspired the work?

“The way I looked at it, if I got to stay here… just to prove that I’m innocent, then so be it.” It was Kalief talking about what he was thinking back when they would keep him in solitary, and deny him court dates, continuously for three years. They would say, “if you plead guilty, we'll give you a lesser charge and you can go free today. You can go home today right now.” And he was like, “no.” It really shows his nonstop fight in the face of this overbearing, institutional monster that was trying to take away everything that he was. People forget that he was 17, 18, and 19 when this was going on. For a kid to have that much fortitude and clear perspective—that’s amazing. He fought for his truth and for his humanity, even up to the point where it became too much for him. He eventually took his own life, but so much of that strength comes through in that quote. You know, it's something that I don't think many of us would be able to do. For five years, he fought against things that would break most of us in five months.

That is such a crucial piece of this. And why it's so important that you are bringing your artistry to this story. It’s absolutely tragic that it was two weeks before his seventeenth birthday when he was arrested. He was a baby, you know what I'm saying? The fact that our children, our babies, are being put in cages in this way, in ways they wouldn't even allow animals at the zoo to be treated. It’s part of the tragic story of America.

It’s not just the tragic part of the story though. It's also the heroic part, and everything that Coby touched on—the fact that Kalief stood up in ways that are unimaginable for most people. 97% of the people who are offered a plea deal take it, and plead guilty for things that they often did not do. I relate to it specifically, because I've been charged with the same things that he was charged with. I've been wrongfully arrested more than once. I've been to Rikers many times. And although the time that I was wrongfully locked up was a drop in the bucket compared to his experience, it gave me some insight into what he was going through.

In addition to the fact that I spent about 10 years at Rikers, I was doing work with young folks to give them an opportunity to use the art center there. They have education opportunities with college students at Columbia, NYU, and the New School. When I watch Time: The Kalief Browder Story, the brilliant film about his family, his life, and his struggles, you know, I'm remembering all those places. The Robert N. Davoren Center at Rikers, all these buildings that I was in for a decade of my life. It cannot be forgotten. I think it is the job of artists to make sure that these stories are told, and that we not only change the narrative but also tell these stories in the right way.

With the sculpture, I wanted to break past the watered-down perceptions that most of the public has about what happens during imprisonment, what happens with people that are awaiting trial. A lot of people out there have this idea of innocence until proven guilty, that you're not incarcerated until you have trial. You know America, we wouldn't do that. I don't want to get too deep into the entire structure of capitalist society, but it’s a money-making scheme. If you're not rich enough to pay, you're just going to stay in jail. It’s insane.

Something with your sculpture that really impacted me was the fact that you could see into the space, like a glass house. Too many people—millions of Americans—never look in, past the block and cement walls.

What you're talking about—the opaque walls of the prisons and the prison system, both physically and metaphorically—is the reason that so many people on the outside have a skewed perception of what goes on inside, and what it's like for human beings to be in this kind of institution. One of the intentions for making this solitary prison cell transparent was so that the viewer could see into it, and have a visceral reaction to what it's like for a human body to be kept in this enclosure. One of my main goals was to wake people who need to be woken up. I don't call myself an activist-artist, but I hope that my work inspires people to, at the very least, take note of reality and, at the very most, do something to change it.

I would love to hear from everybody about how they think about their work in relation to activism. It's interesting, Coby, that you say you're not an activist-artist but want certain outcomes when people view your work. I actually wanted to be an activist ever since I was 18. I read works by Che Guevara, and I was sold. You know, I want the public art that I make with other artists to activate social change, radical justice. To do more than to just incite dialogue.

I think that art and activism can be separate, different things, and that they can also go together. The elders in my life—the people who I aspire to be like, who raised me—were very much some of both. Harry Belafonte is a mentor of mine, and his mentor was Paul Robeson, who said that artists are gatekeepers of truth. Robeson talked about artists as people who don't necessarily lead the movement, but should be working to uplift movements for social justice. Art is many things. It can be just pure expression and extension of the soul; it can be a tool of resistance. I think about art as being like an alarm clock, right? It should liven your senses, wake you up to your humanity and the humanity of others. For me personally, working around prisons has been at the core of my art. I’ve dedicated most of my working life to the movement to end mass incarceration. That's my path.

Bryonn, I forget that we have Gina Belafonte in common. I'd love for you to say a few things about your art.

Absolutely. The production that I've done most recently, and had an opportunity to tour around the world, was developed in prisons around the country. It tells my story, and also a story of a friend who has been locked up for over 29 years in Texas for a crime he didn't commit. What got me excited to create the work—which brings together hip hop, spoken word, theater, Calypso and comedy, through our letters and our lyrics—was really his story, and the idea that I could use my public forum to shine some light on what's going on with my brother.

That power has always struck me as something truly amazing. Artists can get butts in chairs, bodies in the room. You know, Mr. Belafonte talks about the call he got from a guy named Martin when he was 26 years old, and Martin says, “I need some help with this movement thing that they want me to lead. And I know you can help me drive home the point.” Harry was the first person to sell a million records in 1956, and the movement needed help expanding consciousness and raising money. So there are very practical ways that artists can actually, you know, offer their support.

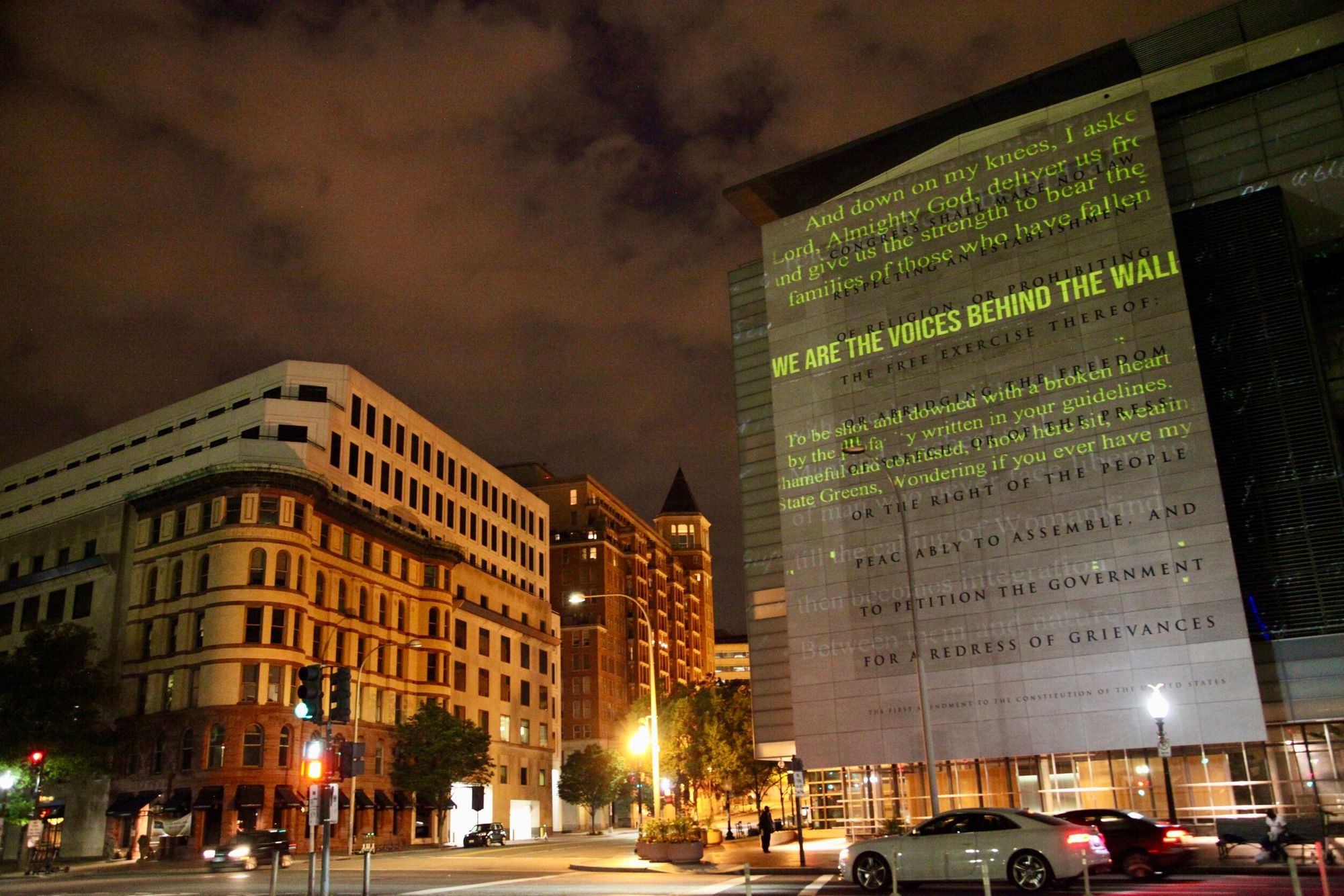

Sam, can you talk about your work as a producer on the Writing on the Wall project with us at For Freedoms?

As someone who wants to uplift other people's work in the public realm, I try to always question: what is the intention, who is your audience, and what is going to ultimately be the impact? One of my favorite things about working with artists and organizations like Incarceration Nations Network is that I’m collaborating with people who wish to seek social and political change.

I've only scratched the surface with Negative Space, but what I’ve seen has opened my mind to new possibilities as an artist. So, I think that's part of the mission, part of the work—not just for other artists, but for our audiences in general—is to open minds to possibilities that we otherwise might not see as being there.

Coby, talk about the generational element of your work. Much like Bryonn, there are artists in your background.

Generational, yeah. I grew up with people who lived and breathed art. Both of my parents are practicing artists. My dad was a Dean of the Art Department at Howard University, so I grew up on that campus. I grew up thinking that this is what kids do. They go into these rooms and they draw big naked people standing on pedestals. I was on the art track throughout elementary and middle school, and went to an arts high school, Duke Ellington School of the Arts, in DC. From there, I went to college, and directly into the design and arts world. I feel lucky for that because of the way that things are coming around right now, where genres are disappearing and barriers are breaking down. You have all this cross-pollination and intersectionality between these creative fields and social, real life fields. Everything's melding into one another and that's what leads me to make the work that I make.

One time when I was six years old, I asked my mother if there were monsters in the world, and she said, “Yes, there are. You know, Coby, if you had come from a place where there were no horses and suddenly you saw a horse, you would think that horse was a monster.” In my mind, it was like [explosion noise]. She taught me that there were different perspectives that you could look at something from, and that common sense is only the agreed upon reality. So I feel lucky growing up in that bubble, coming from all those creatives.

I think that we're lucky to be at this time right now, where, like I was saying, everything's cross-pollinating. Information travels so fast and wide that the ability for a single person to have an effect on society is exponentially greater, I feel, than it used to be. Which brings me to what you were asking, Sam, about why I shy away from calling myself an “activist-artist.” I see myself as a ‘reality artist.’ They say, “learn the rules so that you can break them later.” I want to know what the reality is, so I can break those rules. So many of us carry the weight of the world with us. So much of societal ills come from those subjective realities, when we can't get on the same page. Often I see people who are pushing for activist art to try and tear down dogma, but they tear down that dogma by instituting their own dogmatic ideals.

I define myself as a reality artist if anything, and with this piece especially, I knew from the jump that there are a lot of people who do not want to see a jail cell in front of them. There are people in the activist world who would also be against the piece for aesthetic reasons, even though we’re pushing for the same thing. It was enlightening, at the first For Freedoms town hall, to hear about how people from the Red Hook Community Justice Center’s Peacemakers program were against the piece at the outset, because the question was, why do we need to have this put in front of us when there's already so much pain around this subject here? Afterwards, people had a chance to walk around the piece, feel it and understand it. They understood that there's a large contingent out there that needs to realize the realities of this. There's a certain risk, and there's a certain responsibility. There’s a fine line between impactful art and trauma porn. For artists like me, the kicker is the reaction and the connection with the viewer.

I think I'm getting slightly more comfortable with the title activist. I guess my activism and my creativity as an artist is about convincing the world, and myself, that this body is of value intrinsically. Not because it's special, but because I'm a human being. I guess every breath for me is an artist statement.

You just reminded me of the opening to Mos Def's Black on Both Sides, one of the greatest hip hop albums of all time. And he said, people think they got value because they got money and expensive cars, fancy clothes on, are you valuable? Because you were created by God, you are, you know, because you're a human being, right? You know, that value that you have is intrinsic. I love that. And I also think, you know, that sometimes the conversations that make us uncomfortable are the ones we need to have most. We need to have a certain amount of transparency with what's happening in New York City. We're still paying 10 times the amount per young person to incarcerate folks at Rikers, compared to what we put into the public school system, right? You know, 10 times, over $150,000 to keep a teenager. The 16-to-19-year-olds locked up at Rikers Island. And in the public school system, in New York city, we're paying, you know, $10 to $15,000 per student. We need to look at that in a transparent way.

So I want to close with a final thought, that I think part of the brilliance of Coby’s work is that it brings transparency into the discussion in a way that is moving, in a way that is breathtaking, that is urgent, that honors the legacy and the activism of Kalief Browder. So I want to say thank you for the work, brother, and thank you for the opportunity to be in conversation with you all today.

Thank you, Bryonn. Thank you very much. I'm moved by every aspect of this project, initially by the subject itself, by Kalief and his story and everything that he went through. And I'm moved by everyone involved in the project, who helped facilitate it. Whenever I make work, one of my fears is that it will be taken at face value as art that, you know, somebody made to go in a gallery somewhere. But with this project, especially, I love that everyone involved saw beyond that.

I think one of the biggest measures of success of the piece is that it brought in a sustained partnership with Red Hook Community Justice Center and Pioneer Works itself. And you also were able to give Devon Simmons a platform to be a moderator, because he has this amazing ability to translate art. The whole concept of Negative Space is the space that you don't really see at the forefront, but it helps positive space come through. It’s the little relationships and connections that people make, which are not really public, that are important down the line.

I appreciate all the work that you do, Sam supporting us and bringing our work to reality to the public. And I'm very proud of Coby. How many years have you been working on this piece?

It first sparked off about three, four years ago.

Yeah, and it's a work that is both very personal, but it's also about all of us, in a way. It's like a specific mastery that you've spent, you know, decades perfecting. I’m also grateful for Pioneer Works for giving us space to have these conversations, and seeing that no artist's practice actually stops in their studio. The practice lives on and expands in the hearts and minds we touch in our work. So I'm in gratitude and joy and pleasure and fear and sadness about the opportunities we have, but also the work that we have to do. ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast