Media Burn: The Making of an Image

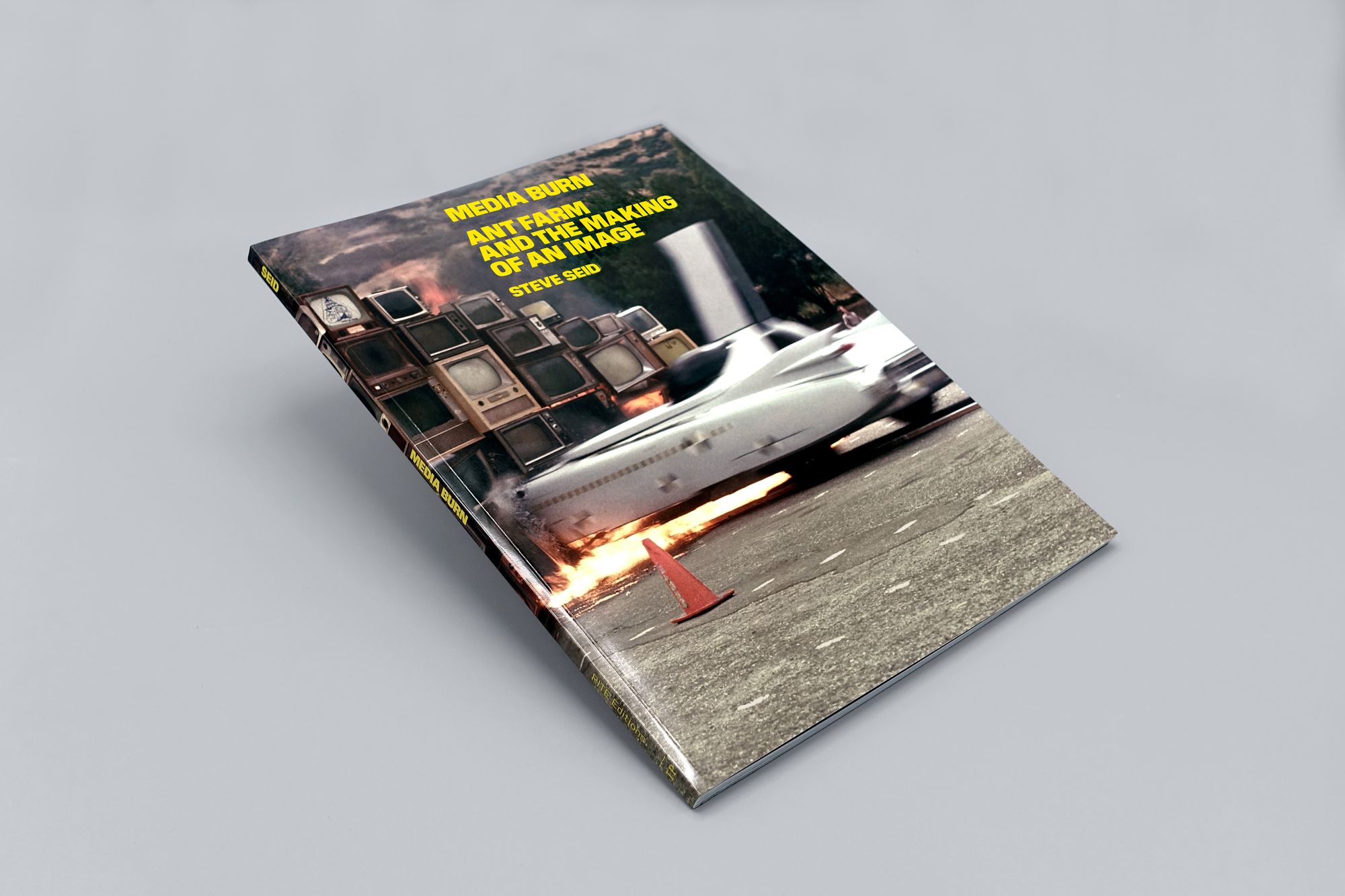

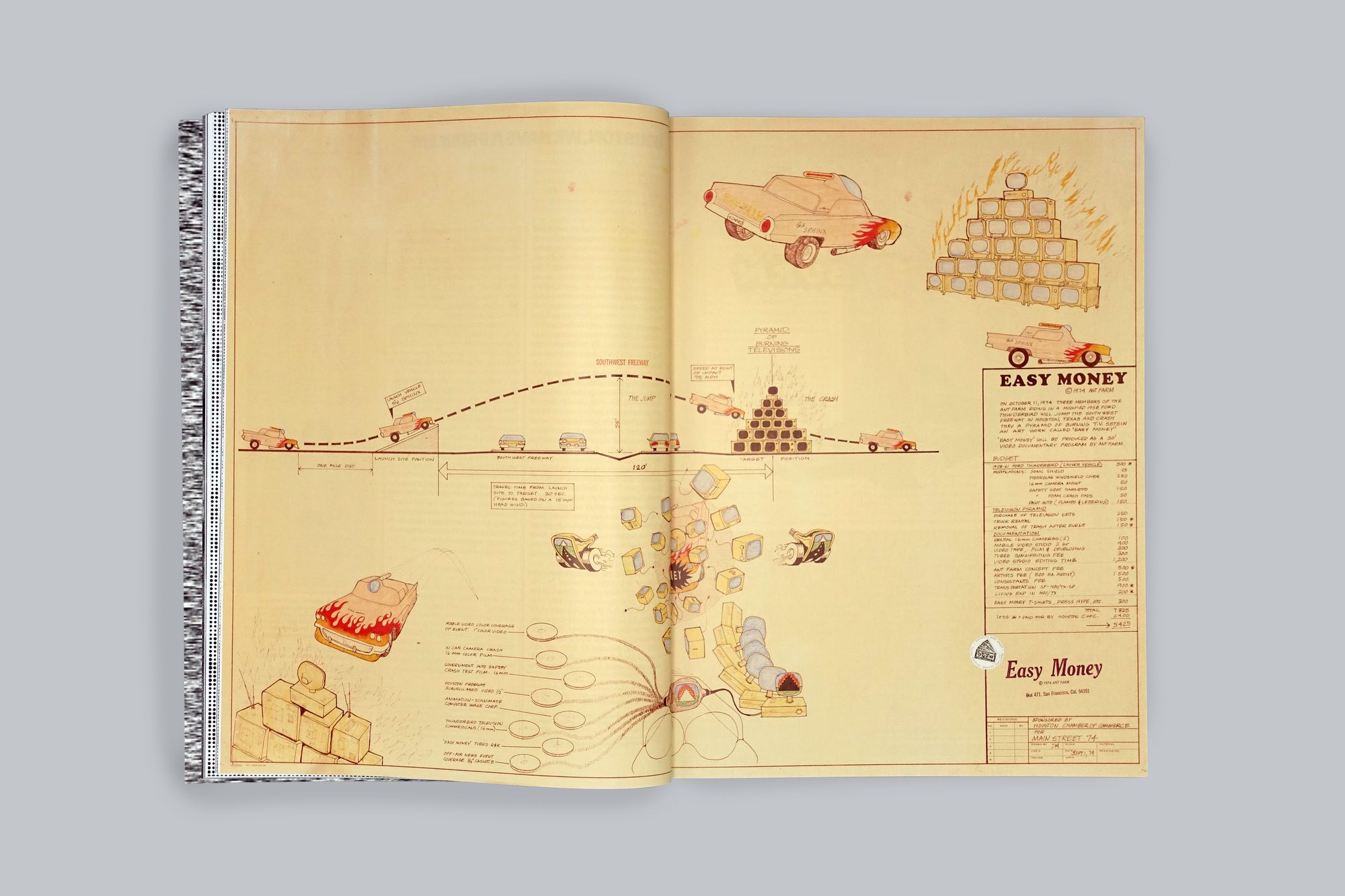

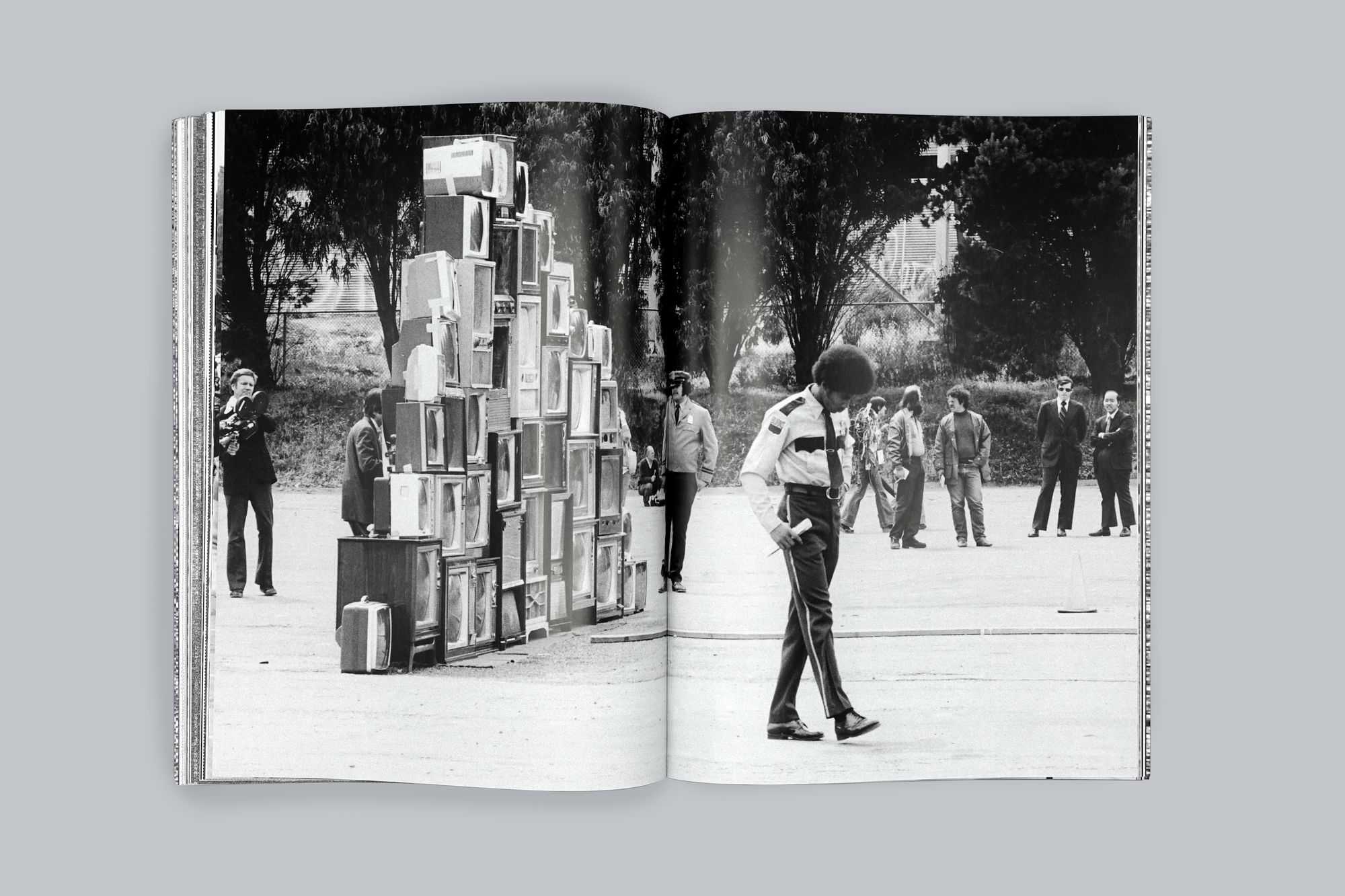

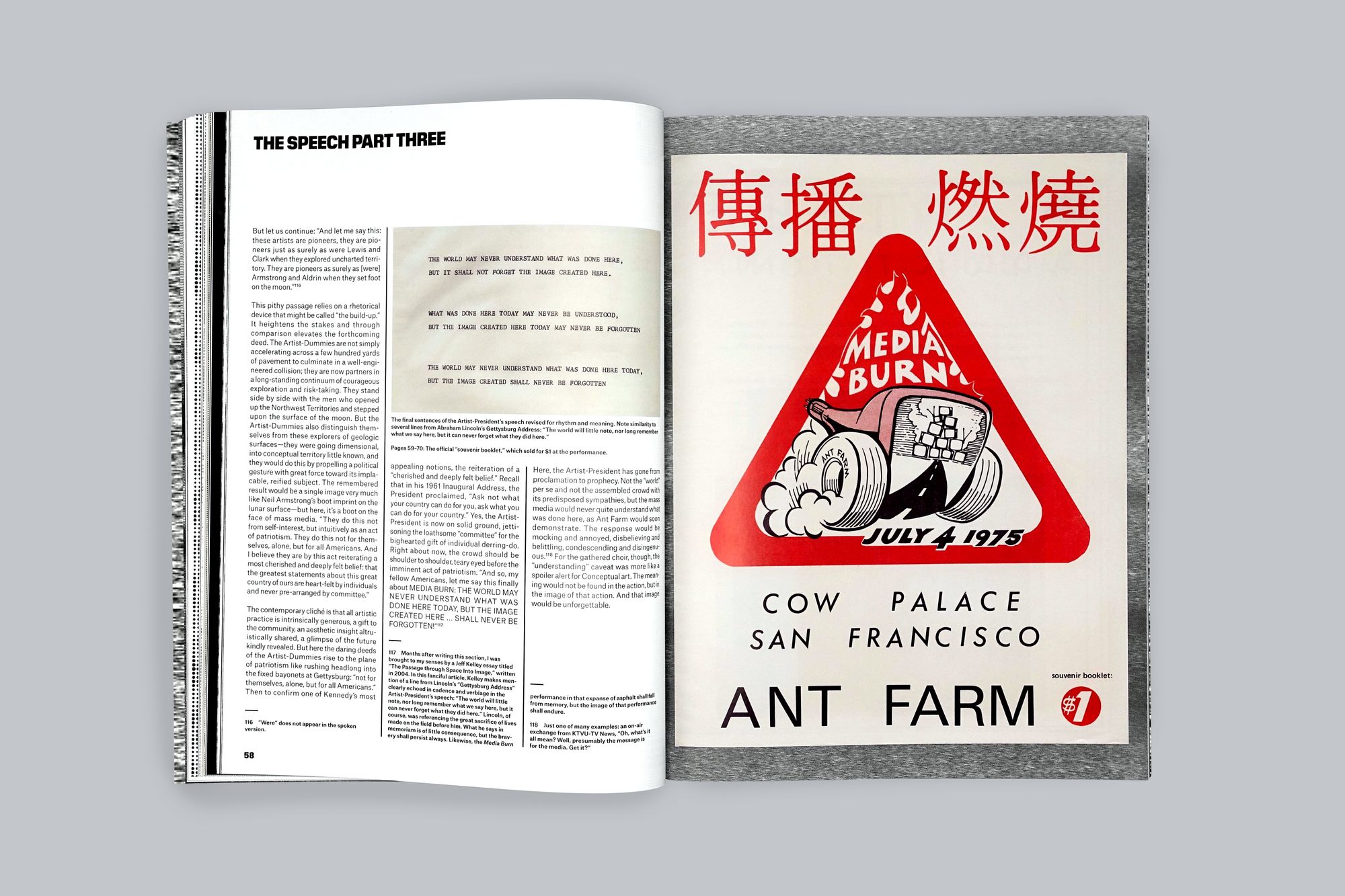

Nearly five years ago, Pioneer Works presented the exhibition The Present Is the Form of All Life: The Time Capsules of Ant Farm and LST, which explored the time capsule projects of seminal media art and architecture group Ant Farm. Ant Farm's work remains more relevant and groundbreaking than ever. We're sharing a particularly prescient excerpt from the recent Media Burn: The Making of an Image by Steve Seid (2020, Inventory Press). The book documents Ant Farm’s legendary 1975 performance, in which a radically customized Cadillac was driven through a wall of burning television sets. Media Burn is a vibrant assessment of the complex set of cultural references and art-making strategies informing this collision of twentieth-century icons. Author Steve Seid probes the little-known critical backstory of this bold performance (and resulting video work) and its irreverent effort to mount a subversive critique of media hegemony while reimagining the core meaning of performance itself. This especially remains true for the performance's"Artist-President," a Kennedy-esque figure whose bombastic speech began the proceedings. Read more about the history of the creation of the Artist-President and watch footage from the 1975 performance itself.

Selecting the Fourth of July as detonation day opened up dramatic new possibilities for Media Burn. Previously, there was “just that spectacle: But Independence Day would be nothing without “the tradition of a politician speaking at a Fourth of July coaxing the question: “Who might this rousing speaker be?”

Ant Farm had several allies, aligned spirits who could be called upon to bail out unwieldy collective projects. TVTV was certainly one, as was Optic Nerve. T. R. Uthco, or Truth Company, was another. Composed of three artists—Doug Hall, Jody Procter, and Diane Andrews Hall—and a fourth occasional member, John Hillding, T. R. Uthco was founded in 1970 after its members moved to San Francisco following graduate studies at the Rinehart School of Sculpture of The Maryland Institute. Some of T. R. Uthco’s earliest interventions involved parodic restagings of performance art that they dubbed “Great Moments.” According to a January 4, 1975, issue of Artweek, “nearly every major performance artist from Acconci to Wegman receives a tasty conceptual pie in his or her face before the last Great Moment has passed.”

In the fall of 1974, Hall and Procter began developing a new performance character, the presidential personality. Procter would write blustery speeches that Hall would deliver with all the overblown gestures of a pompous The generic Artist-President soon solidified in a figure identifiable as John F. Kennedy. Hall was quite familiar with JFK’s executive comportment, having unleashed impressions of him since his college days at Harvard. The impersonation came complete with the famed Boston accent. Add the wizardry of a makeup artist and Hall could do an uncanny Kennedy.

Obviously, John F. Kennedy was no neutral figure; he was beloved, mourned, and idealized—the stuff of a generation’s trauma. Twelve years after his assassination, Kennedy remained an open sore on the skin of American democracy. To do a send-up of JFK was rash to some, vulgar to others, but usefully jarring and pointedly iconoclastic when performed with thoughtfully barbed

The presence of Doug Hall as the Artist-President at Media Burn would elevate the proceedings, adding much-needed complexity to the whirlwind of errant signifiers: the Phantom Dream Car, towed along by the myth of upward (or at least linear) mobility; the Artist-Dummies, sacrificial pilots on a one-way trip to mediated oblivion; and the blazing pyramid of television sets, one of the seven wonders of modern manipulation.

Ascending the stairs of the bandstand, the Artist-President would issue his edifying address, establishing a tone and purpose, while focusing the gathered crowd’s attention on the image to be created here. “And so my fellow Americans, let me say this finally about Media Burn...” Depending on where you look, there are lots of words, most penned by Chip Lord with revisionist advice from Doug Hall and Jody Procter, as well as from external sources that were quietly tapped.

There is the speech by the Artist-President before an aghast but amused audience, and the longer, more pointed version printed in the $1 souvenir booklet. There is a “first draft” lacking the tone that would soon surface and a satiric speech that would have significantly altered the reception of the event, which was (wisely) There even survives, on a sheet of paper, the speech’s closing lines repeated thrice with minor variations, trying to establish not just the meaning but the cadence of the Artist-President’s finale. As found in the souvenir booklet, the speech appears as a two-page spread, brazenly printed on blue White House stationery with a Presidential Seal and John F. Kennedy’s signature. The impersonation begins here, donning the legitimacy and force of an official document and, better yet, making the wild surmise that if in fact the president were here to deliver a Fourth of July crowd-pleaser, this is what he would have authored. There is something almost presidential about the valiant verbiage, for these are the actual words of someone who was almost president, George S. McGovern, a standing U.S. Senator from South Dakota. The first half-dozen paragraphs in the Artist-President oration are either verbatim borrowings or close imitations of McGovern’s essay, “State of the Union,” published in the March 13, 1975, issue of Rolling Stone. A stalwart antiwar activist, McGovern had run against Richard Nixon in 1972. His grassroots campaign failed to gather the necessary votes and his vice-presidential running mate, Thomas Eagleton, plunged the ticket into scandal when it was made known he had been treated for depression.

Defeated or not, Senator McGovern still held unexpectedly progressive views, even more necessary to voice now that the country was burdened with the Gerald Ford presidency. To counter Ford’s January 15, 1975, State of the Union address, Rolling Stone brought McGovern on board as their respondent. “In this issue,” they declared, “George McGovern assumes the role he rejected in 1972 as the principal spokesperson of the Democratic party by writing a State of the Union message considerably different than the one deliver[ed] by President Ford in January.” The operative phrase here is “assumes the role.” With artistic fervor, Doug Hall as the Artist-President was also assuming the role. What could be more fitting, literally, than to lift the very words of a fellow impersonator?

McGovern’s State of the Union is a clear-eyed, left-leaning critique of a country burdened by an unworthy an inflationary economy, maldistribution of wealth, aggravated energy dependence, and, ultimately, the unshakeable sway of what he termed “economic He begins, as does the Artist-President, with the disquieting line, “The American spirit is uncertain.” This is a great destabilizing statement, and when uttered by Doug Hall it would swiftly deflate the windbaggery of Independence Day zeal. The Ant Farm speechwriters obediently follow McGovern’s ensuing words, a short list of the bad that has befallen us: “political “economic turmoil,” and “a pervasive doubt about our ability to correct it.” Then a finely phrased corrective: “I believe we can find solutions in our origins.” Here, the breadth of history and the Founding Fathers are invoked: “Our nation comes from a revolution against political tyranny. Now we must finish that revolution by replacing the structure of economic privilege and by repudiating the tyranny of the warmakers and the moneymakers.”

Then another pithy phrase that rings in the ear: “What has happened to us is not a random visitation of fate.” For emphasis Ant Farm swaps out words, substituting “What has gone wrong with America is ...” This verbal maneuver leaves behind the individual for a body, a body politic now ailing. “It is the result of forces which have assumed control of the American structure—economic royalists as oppressive as the Crown 200 years ago. These forces are militarism, monopoly and the maldistribution of wealth.”

But now Ant Farm begins asserting their new direction by nixing the “maldistribution of wealth” in favor of “and the mass media.” With several thousand more words in his State of the Union address, McGovern had time to broach a plethora of ills, from domestic spying by the CIA to trickle-down tax cuts, from the SALT treaty to antitrust laws, from the corporate food chain to rising unemployment. Anxious to engage their eager audience, Ant Farm would bring the mass media front and center from the podium while staying closer to the Senator in the souvenir booklet: “Militarism depletes our economy because it still dominates our foreign policy ... The arms industry consumes our resources but returns nothing to the national wealth. But foremost, our expanding militarism is morally wrong. AND I SAY IT IS TIME TO SAY NO TO THE MILITARISTS!”

This should be an award-winning compression algorithm. Ant Farm retains the spirit of McGovern’s antimilitary rant, but the rhetorical distance between their opening line (“Militarism depletes”) and their rousing finale (“NO TO THE MILITARISTS!”) is an additional 750 argumentative words. Ant Farm then continues: “The second force disrupting our country is Monopoly. Today just 200 corporations control nearly two-thirds of America’s manufacturing assets. Not only economic control of markets, but political control to guarantee themselves a privileged position. These monopolies often dominate government regulatory agencies which are supposed to protect the citizen. And this too is morally wrong. NOW I SAY IT IS TIME TO END MONOPOLY BY BUSINESS RULERS!”

The above argument also heavily truncates McGovern’s grand unraveling of the injustices levied by the “economic royalists.” By broaching the two previous perils, militarism and monopoly, Ant Farm is able to broaden the context of Media Burn. Though the main target is mass media, they gain scope from this collateral critique of other systemic ills. A more sweeping statement also lends weightier credibility to the final, unforgettable statement.

After abbreviating the speech thus far, the Artist-President resumes. He is now ready to reveal his real intent, to lambast the mass media.

Television because of its technology and the way it must be used can only produce autocratic political forms, hierarchies, and hopeless alienation. Mass media monopolies control people by their control of information. In our vast society, it is virtually impossible to escape the influence of commercial And who can deny that we are a nation addicted to television and the constant flow of media? And not a few of us are frustrated by this Now I ask you, my fellow Americans, haven’t you ever wanted to put your foot through your television screen?

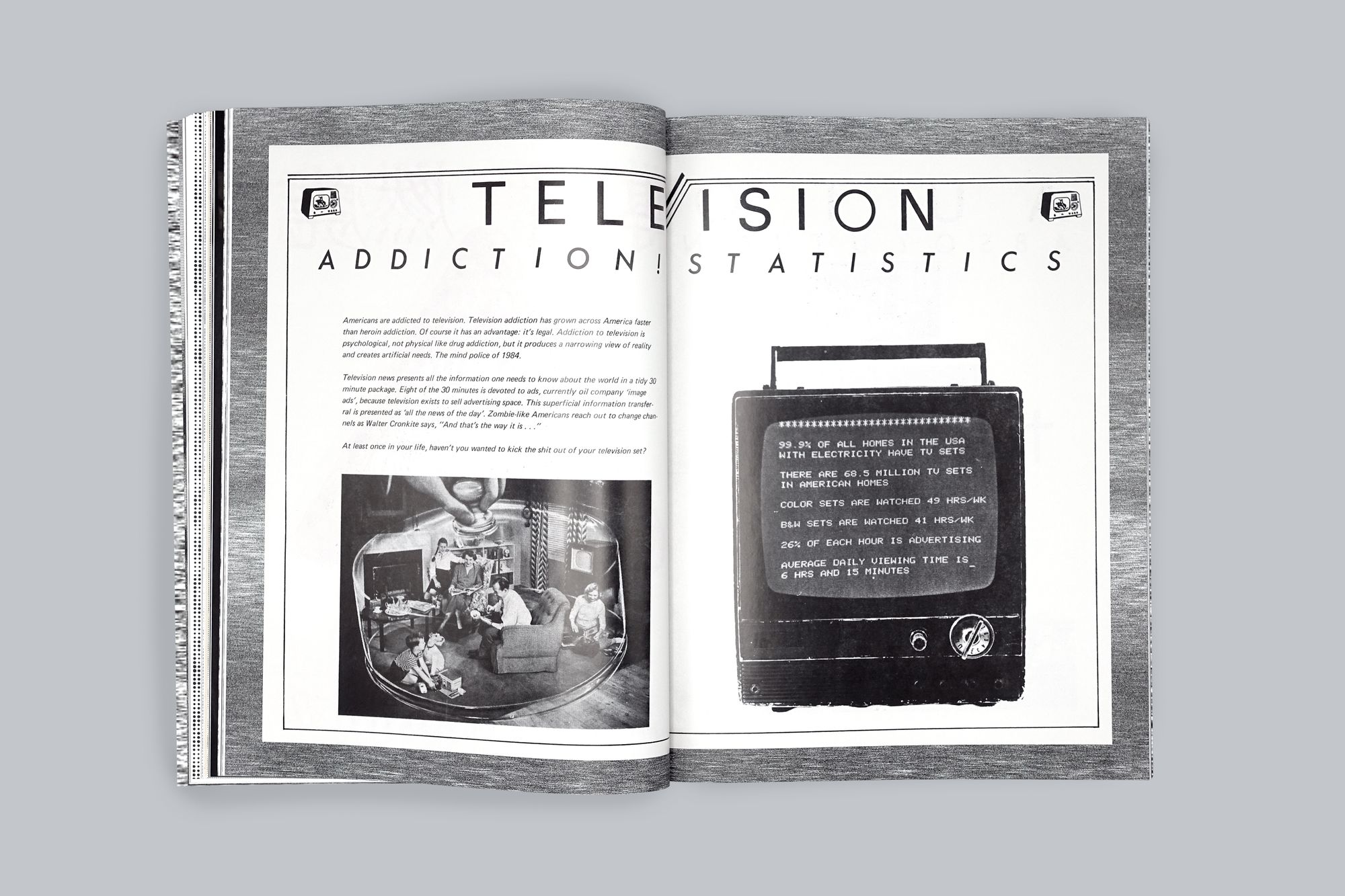

This was not a rhetorical question asked by our Artist-President. If, as was said in the souvenir booklet, “99.9% of all homes in the USA with electricity have TV sets,” this assured that many (if not all) members of the audience, presumably standing on two feet at that very moment, had at least one foot they wanted to propel toward their TV screen. The commonality being TV ownership, the shared political orientation being infuriation, this was, in effect, an appeal to mobilize the audience’s frustration with the Tube.

Jerry Mander’s influential book, Four Arguments for the Elimination of Television, would not be released until 1977, but its influence rode upon a preexisting cultural “Kill Your Television” was already a favored slogan; FCC Chairman Newton N. Minow had long ago declared television to be a “vast wasteland”; the TV-Turnoff Week had been launched in 1974; grassroots movements would rally around such books as Raymond Williams’ Television: Technology and Cultural and anti-television groups like White Dot would gain followings decades after Media Burn.

In the coming videotape version of the performance, Doug Michels, wearing his Artist-Dummy jumpsuit, would reinforce this notion, stating in an impromptu interview: “If everyone in America would burn just one TV set ...” “Now I ask you, my fellow Americans, haven’t you ever wanted to put your foot through your television screen?” Not just a question, but a question issued in the unique Boston tempos of a dead president. On the bandstand between strips of patriotic bunting, a television console was mounted where the presidential seal might hang. Yet this affixed screen was as dead as the president himself—the Commander-in-Chief of the Televisual, expired. With the ideological underpinnings in place, the Artist-President could shift his attention to the imminent spectacle, the Artist-Dummies and their date with destiny. “Today there stand before us two media matadors, brave young men from Ant Farm who are about to go forth into the unknown.”

But I must stop here and correct a misattribution. In the souvenir booklet, this section of the speech begins with an elaboration, explaining the “media matador” reference: “As Robert Blake wrote about matadors: ‘Bullfight critics row on row crowd the enormous Plaza de Toros, but only one is there who knows, and he is the one who fights the bull.’”

There is attribution for the poem, titled “Bullfight Poem,” translated from Spanish by Robert Graves, famed poet and classicist. Graves was fluent in Spanish, having lived in Majorca for decades, and in his masterwork The White Goddess (1948), he writes about the origins of the cult of bulls that migrated from Rome to Spain. It is also known who wrote the original poem: the famous bullfighter Domingo Ortega, who was an active matador throughout the thirties and forties.

This poem has a peculiar history of mistaken identities, and Ant Farm joins this fine tradition. In an April 11, 1971, letter to the editor of the Washington Post, Congressman F. Edward Hebert wrote, “President Kennedy was fond of quoting some lines from the Spanish poet Garcia Lorca,” and followed with the Ortega poem. Kennedy, in fact, did quote the poem during an October 16, 1962, meeting with the National Foreign Policy Conference for Editors and Radio-TV Public Affairs Reciting from memory, Kennedy misquoted the poem itself: Bullfight critics row on row / Fill the enormous Plaza de Toros / But only one is there who knows / And he is the one who fights the

How Kennedy came to know this poem is explained in yet another letter to the editor, this time to Life magazine on August 6, 1965. “Can Mr. Schlesinger give us the name and author of a favorite poem of John Kennedy that referred to the matadors and the bulls?” the writer asks. After the verse in question is presented, Arthur Schlesinger Jr. replies: “The author is Bullfighter Domingo Ortega who, at the time of the Bay of Pigs disaster, sent a signed photograph to Kennedy with these lines inscribed as a gesture of sympathy and encouragement at what he felt was a difficult moment for the President.”

The Bay of Pigs took place in April 1961; Kennedy’s off-the-cuff use of the poem was delivered during the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962. This simple bit of doggerel explains much about the horns of a dilemma. It is only the man in the arena, facing the bull, who can truly understand the implications of the cape and the consequences of the sword. And it is only by standing upon that bloodied circle of soil that you can suitably respond to the stunning fury of the moment. By quoting that poem during a time of crisis, Kennedy was overtly requesting some sympathy for the man in the ring, himself.

A dozen years later and the “Bullfight Poem” would once again be thrown about by Kennedy, this time in impersonation. And the “two media matadors, brave young men from Ant Farm” would stand not in the Plaza de Toros but in the Cow Palace parking lot facing a very bullish mass media. But let us continue: “And let me say this: these artists are pioneers, they are pioneers just as surely as were Lewis and Clark when they explored uncharted territory. They are pioneers as surely as [were] Armstrong and Aldrin when they set foot on the

This pithy passage relies on a rhetorical device that might be called “the build-up.” It heightens the stakes and through comparison elevates the forthcoming deed. The Artist-Dummies are not simply accelerating across a few hundred yards of pavement to culminate in a well-engineered collision; they are now partners in a long-standing continuum of courageous exploration and risk-taking. They stand side by side with the men who opened up the Northwest Territories and stepped upon the surface of the moon. But the Artist-Dummies also distinguish themselves from these explorers of geologic surfaces—they were going dimensional, into conceptual territory little known, and they would do this by propelling a political gesture with great force toward its implacable, reified subject. The remembered result would be a single image very much like Neil Armstrong’s boot imprint on the lunar surface—but here, it’s a boot on the face of mass media. “They do this not from self-interest, but intuitively as an act of patriotism. They do this not for themselves, alone, but for all Americans. And I believe they are by this act reiterating a most cherished and deeply felt belief: that the greatest statements about this great country of ours are heart-felt by individuals and never pre-arranged by committee.”

The contemporary cliché is that all artistic practice is intrinsically generous, a gift to the community, an aesthetic insight altruistically shared, a glimpse of the future kindly revealed. But here the daring deeds of the Artist-Dummies rise to the plane of patriotism like rushing headlong into the fixed bayonets at Gettysburg: “not for themselves, alone, but for all Americans.” Then to confirm one of Kennedy’s most appealing notions, the reiteration of a “cherished and deeply felt belief.” Recall that in his 1961 Inaugural Address, the President proclaimed, “Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country.” Yes, the Artist-President is now on solid ground, jettisoning the loathsome “committee” for the bighearted gift of individual derring-do. Right about now, the crowd should be shoulder to shoulder, teary eyed before the imminent act of patriotism. “And so, my fellow Americans, let me say this finally about MEDIA BURN: THE WORLD MAY NEVER UNDERSTAND WHAT WAS DONE HERE TODAY, BUT THE IMAGE CREATED HERE ... SHALL NEVER BE

Here, the Artist-President has gone from proclamation to prophecy. Not the “world” per se and not the assembled crowd with its predisposed sympathies, but the mass media would never quite understand what was done here, as Ant Farm would soon demonstrate. The response would be mocking and annoyed, disbelieving and belittling, condescending and For the gathered choir, though, the “understanding” caveat was more like a spoiler alert for Conceptual art. The meaning would not be found in the action, but in the image of that action. And that image would be unforgettable.

Subscribe to Broadcast