The Troubles I've Seen

On a hot and humid day in late July, the artist Le’Andra LeSeur and I zipped along in our Alpine-style, aerial cable car at a brisk 1,378-feet-per-minute, high above the lush treetops of Atlanta, where we’re both from. Slightly afraid of heights, I grew queasy as our little glass cabin of death floated above Stone Mountain’s water-streaked granite cliff face. Growing up, I could see the 825-foot egg-shaped, Martian form rising over the surrounding freeways, like a moody creature bursting from Earth’s primordial core. The result of continental plates colliding over 300 million years ago, the formation was created from a giant pool of molten magma miles deep inside the Earth, which cooled over time. The land around it was slowly stripped by erosion, exposing what early Native Americans called Rock Mountain.

We slowly passed the massive bas-relief sculpture of men on horseback cut 42 feet deep into the mountain’s side, larger than Mount Rushmore at more than three acres wide. A woman wearing a Stone Mountain Park-branded uniform intoned over the gondola’s sound system: “From left to right we have Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee, and Thomas Stonewall Jackson. Each man is shown here on his favorite horse. Davis is on Blackjack, Lee is on Traveler, and Stonewall is on Little Sorrel.” The park employee had likely recited this script several times the previous hour, with all the cheer of a gravedigger. iPhones held high, the crowd uttered a “wow.” What was omitted from our attendant’s spiel was that the men on horseback were all Confederate generals, the entire park a monument to their efforts maintaining an agrarianism built on the backs of enslaved Black people bought and sold like cattle.

When LeSeur and I both went there as kids—me in the ‘80s and ’90s, her in the early aughts—the park was a strange amalgam of state park and local Disneyland. I’d ride the steam-powered railroad, which was always attacked by hatchet-toting actors in Indian costumes. I’d join my family, all of whom are white, to watch the nightly laser light show animating the Confederate generals to the tune of Elvis’s “Dixieland.” My dad and stepmom even got engaged there. When I recalled this memory to LeSeur, who is tall and genial with a ready laugh, she related how her own family, like many other Black households from nearby Stone Mountain Village, grilled hamburgers in a meadow at the mountain’s base on weekends. At that point the place had become a highly popular Atlanta institution, with most folks thinking nothing of its racist symbolism. As children, LeSeur and I were blissfully unaware. Today, as Confederate monuments nationwide are being razed, the fact that this one—literally the biggest of them all—is still standing and beloved by both Blacks and whites alike makes it a confounding paradox in the cradle of the progressive New South. LeSeur told me that leaving the sculpted outcropping unaltered was mandated by state law, and convincing Georgia’s Congress to repeal it would be an uphill battle. Even some Black lawmakers contend they shouldn’t be in the business of erasing history. “So I started thinking,” she continued, “how could I collapse it? I couldn’t literally, but I could within myself.”

This is what prompted LeSeur to create a new body of work about the mountain, which debuted in September at Pioneer Works, in the exhibition "Monument Eternal," on view until December 15th. Co-commissioned by Pittsburgh Cultural Trust, it will travel to its Wood Street Galleries next year, and then the Tulsa Artist Fellowship, where LeSeur’s currently in residence. At the time of our meeting in Georgia, she had just shot a video on the summit and was planning on making gestural drawings reflecting her physical and psychological reaction to the site’s history.

Over the previous decade or so, LeSeur’s multimedia work has featured her own body as a mirror of—and metaphor for—the trials of Black experience in America. She often performs simple, repetitive actions in slow-motion, soundtracked to an eclectic array of Black musicians and singers. Emotive and circumspect, her works’ methodical execution and elegant simplicity sets LeSeur apart from the high-volume polemics and noisy aesthetic of some of her peers. One of her video installations was recently acquired by the Whitney Museum, but “Monument Eternal” presents a pinnacle in the career of an artist who dives headfirst—in her Georgia hometown and beyond—into America’s darkest histories.

*

Among those histories is one that began, in Atlanta, in the early morning hours of April 21st, 1913. That’s when the dirt streaked body of 13-year-old Mary Phagan was found next to an incinerator in the basement of the National Pencil Company factory downtown, where she worked. Phagan’s dress had been pulled up over her head, her underwear was bloody and torn, and seven feet of wrapping cord was tied tightly around her neck. “He said he wood love me land down play like the night witch did it but that long tall black negro did boy his slef,” read a note found next to her body. Police investigators initially pinned the crime on the company’s “night witch,” or night watchman, who found the body. Later they changed course, identifying the factory’s Jewish superintendent, Leo Frank, as Phagan’s strangler, based solely on the testimony of the company’s janitor. The police arrested Frank and the case went to trial.

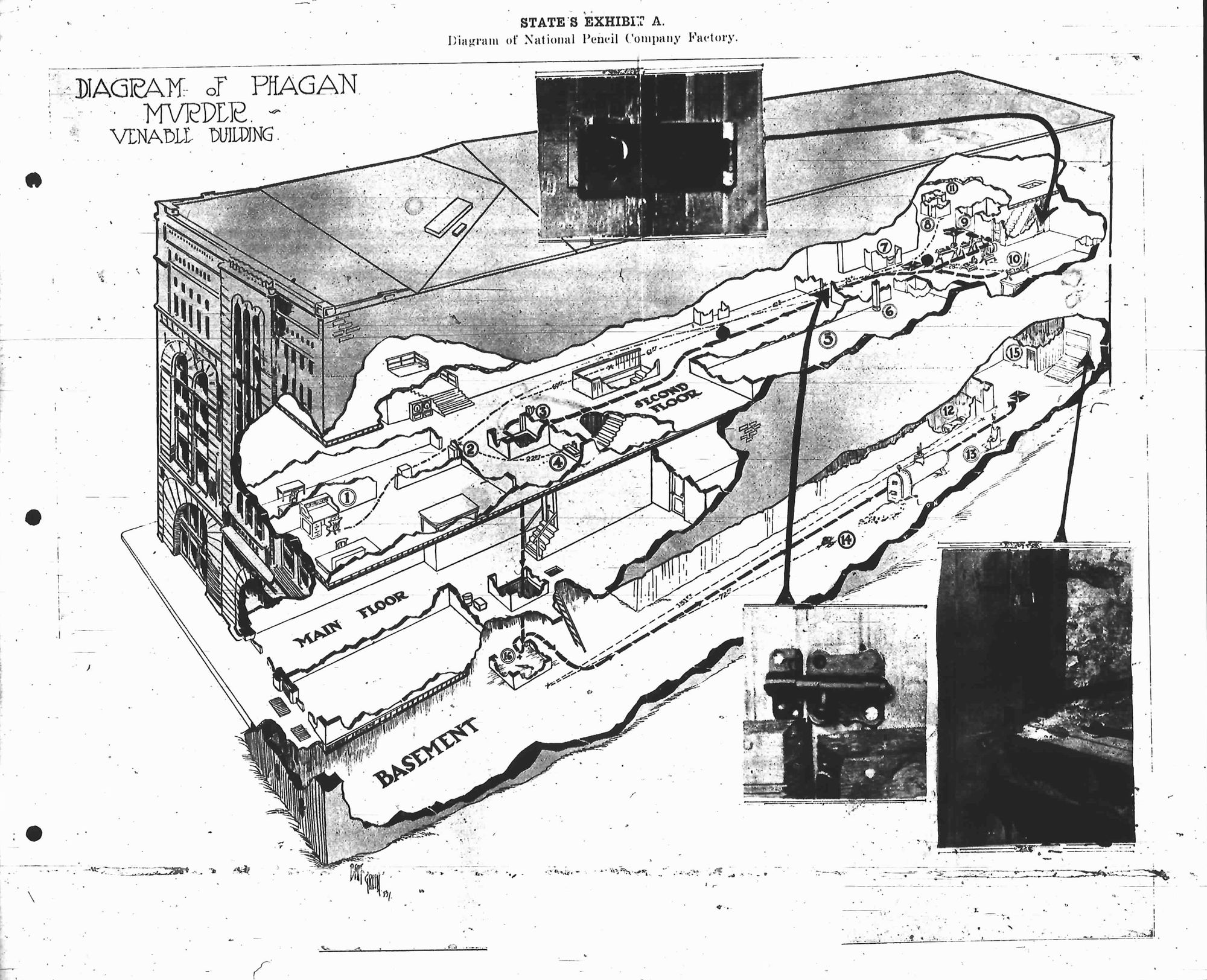

Local newspapers went wild with speculation: “Was Factory Used as Secret Rendezvous?,” “Frank Tried to Flirt with Murdered Girl, Says Boy Chum,” “Police Have The Strangler.” Northern papers pushed back against Atlanta’s anti-Jewish “mob.” In court, elaborate diagrams of the crime scene were labeled “Venable Building,” as the factory-owning brothers William and Sam Venable built it entirely out of granite from their Stone Mountain quarry. Frank was found guilty, the jury swayed by perceptions that the New York City-raised man was a “rich, punctilious, northern Jew lording it over vulnerable and impoverished working women," one scholar has noted. Sentenced to hang, Frank’s punishment was eventually commuted to life imprisonment. Local vigilantes were furious, and decided to take matters into their own hands. They broke into Frank’s prison and drove him to the town of Marietta where Phagan was from. Blindfolded and handcuffed, with ankles tied, Frank was hanged from an oak tree facing the girl’s childhood home on August 17th, 1915.

In the aftermath, local newspapers issued calls to restore order through a reorganized Ku Klux Klan, which had fallen apart in the 1870s after its violence horrified the nation. Watching with interest from the sidelines was a man named William Joseph Simmons. Earlier that year, the physician and fraternal order member had caught a screening of W.D. Griffith’s three-hour paean to white supremacy, The Birth of a Nation. The film depicted freed Blacks terrorizing whites by preventing them from voting, raping their wives, and attacking their homesteads. Coming to save the day was the KKK, burning crosses and lynching Black folk to “sav[e] the Aryan race” from the “anarchy of black rule,” as the film’s intertitles explained. While the original order had exclusively targeted freed Black people, the Frank case laid bare local ire for anyone who didn’t conform to white, Southern nativism. Simmons expanded his new KKK’s bigoted purview to encompass not just Blacks but Jews, Catholics, and anyone else who was deemed alien. After he put an ad in the paper, just months before The Birth of a Nation’s Atlanta premiere, 15 men signed up, including many who were involved in Frank’s lynching and Sam Venable. He let Simmons bring the group by bus from downtown Atlanta to his Stone Mountain property for their very first initiation ceremony on Thanksgiving night, 1915.

When they arrived, they scaled the boulder-littered slopes of the mountain to its peak, passing through woods of oak and cedar. At the top, Williams lit kindling at the base of a 16-foot wooden cross soaked in pitch and kerosene, which went up in flames. It was the KKK’s first use of this type of conflagration and was inspired by the cinematic flourish in Griffith’s film that had been borrowed from an old Scottish signal of war. Bending a knee, the initiates kissed a sword and made a vow to the Klan, “bathed in the sacred glow of the fiery cross,” as Simmons later recalled. Below, in the Black neighborhood of Shermantown—named for the Union general, William Tecumsah Sherman, who liberated its enslaved residents—townspeople could see the burning pyre lighting up the sky. It burned through the night, fanned by a cool Autumn breeze.

*

110 years later, on that same plateau, the sun shines brightly through puffy clouds—as captured by LeSeur’s lens in her video Monument Eternal (2024). She’s dressed in white and there’s no one around, just sky above and naked granite at her feet. Small pools of water fill the stone’s dimpled and ridged surface. The setting looks positively lunar, yet of this world. “Why must I collapse?,” she asks in voiceover, midway through the video, which was filmed in early June using a high-speed camera. The video captures her collapsing, literally, from a standing position, but so slowly that it’s nearly impossible at first to tell what’s happening. Her bare feet are firmly on the ground. A brisk breeze ruffles her locs, which cast deep shadows on the back of her shirt as they rise and fall at a hypnotic snail’s pace. “I have become an insurrection echoing baptism. Because who would’ve known to ask, ‘Do you know this place? Since your breath is no longer here?’” Her feet leave the ground as she falls backwards.

“Black and brown death is every Anthropocene origin story.” The camera is angled low to the ground from behind as her body gains momentum. Her hands and arms slowly rise before her as her weight gives way. Near the end of the video’s seven minutes she is fully in mid-air, her falling so imperceptible that it looks like she’s floating, suspended. The camera has retreated to give a wide, panoramic view of LeSeur hovering at the horizon line, the granite moonscape spreading left and right below her. An endless green forest canopy, hazy with atmosphere, recedes for miles into the distance. Above that, above her, clouds gather in dark pools.

LeSeur begins the video with a closeup of the mountain carving, as if urging the viewer to really look. The monument, which took 58 years to carve, was the brainchild of KKK members in thrall of the Lost Cause theory, which waxed nostalgic for a pre-Civil War era at a time when the region was undergoing rapid change. During the first decade of the new century, workers were flooding into cities like Atlanta. Child labor was rampant. Atlanta’s 1906 Race Riot and the passage of draconian Jim Crow Laws maintained Black oppression. Catholics and Jews like Leo Frank became “scalawags,” synonymous with northern aggression. The first klansmen believed it their duty to protect the white race by terrorizing freed Blacks, and anyone abetting them. For six years in the 1860s they rode hooded on horseback, chasing Blacks through the woods, lashing, hanging, shooting, castrating, quartering, and burning them alive. In 1868 alone, 363 Blacks were murdered across the state of Georgia. The carving’s three generals march proudly forward with their hats held to their chests, honoring this violent protectionism. In Monument Eternal, the voices from a Black choir swell as we look at the relief: “Nobody knows all the troubles I’ve seen.”

When LeSeur and I met up there in July, tourists ogled views of Atlanta through binoculars, men did push-ups to the thumping beat of their jukebox, and kids jumped over rock pools. We walked to where she had laid a mat down on the mountain’s surface while filming Monument Eternal, in an attempt to blunt the impact of her falling over and over again to get the right shot. The cushioning was later scrubbed out in post-production. But even with the mat, LeSeur got a concussion, leaving her brain foggy for weeks. Pain informs the work’s title, borrowed from the memoir of jazz musician-turned-Hindu guru Alice Coltrane. In the book, Coltrane reflects on a time when she couldn’t eat or sleep, leading her to hallucinate and self harm—a period she later considered to be a Tapas, an extreme spiritual trial. For LeSeur, pain is integral to Black experience, and Monument Eternal physicalizes it. “We reach these breaking points where we literally go crazy,” LeSeur told me, influenced by the work of Therí Alyce Pickens, who writes that madness is not a disease or disability traceable to a physiological cause, but rather rooted in the existential fear and oppression of Black people generally. “We weren’t born mad. We were made to go mad.”

We were on a mission that July day to find the elusive Stone Mountain Daisy, Helianthus porteri—a cheery, yellow sunflower that only grows in and around granite—which LeSeur planned to use to make a dye or wash, for drawings in her Pioneer Works exhibition. After staining, she’d rub and smudge the flower into the paper, emulating how she rubbed stress balls when she brought them with her to Stone Mountain. The drawings, then, would be like abstract portraits of her stress response. LeSeur thought she had seen some of the daisies growing by a rock pool. We used an app called Seek that identifies plants and animals simply by pointing your camera at them. I use it whenever I travel somewhere new, just to see what kind of weird shit is growing there.

I trained my phone on a pool full of vegetation with bright, yellow flowers on tall stems rising out of the water. Coreopsis lanceolata. Lance-leaved coreopsis. It wasn’t what we were looking for, so we moved on. Unsure whether what we were about to do was legal, we decided to walk to a more secluded area, to a cluster of large cedar trees. Most of the mountaintop is bare, but there are groves here and there, like oases of vegetation. We stepped over spiny yuccas and fledgling sumacs. Spotting an adorable little twin-eared blue flower on a stem of pretty, flayed leaves, we knelt down to take a closer look. Commelina erecta, otherwise known as Widow’s Tears. We remarked how lovely it was, then passed through a grove of Georgia oak, Quercus georgiana, a very rare species that, like the daisy, only grows on granite outcrops. In a nearby depression was a scraggly bush decorated with hundreds of yellow flowers. I held my phone up to it. Helianthus porteri. Jackpot! LeSeur reached over, then hesitated before plucking a few. “I feel bad about harming them. They're so cute. They're just trying to exist.”

*

LeSeur gravitated to artmaking entirely by accident as a college freshman at Bucknell, studying business while on a basketball scholarship. Students were required to take elective classes in a different subject, and LeSeur chose visual and performing arts because the department arranged trips to New York City, where LeSeur was born and had family still. Her mother, Patricia, had instilled in her a love of music; they’d dance together to Patricia’s jazz records. A freshman art history survey class introduced LeSeur to Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (1917), a mass-produced urinal Duchamp signed with the pseudonym “R. Mutt.” LeSeur was emboldened by Duchamp’s tongue-in-cheek fuck you to conventional standards of artistic skill. Though she didn’t know how to draw or paint, she thought she too could be an artist if she willed it so. She also learned about Carrie Mae Weems, who in the early ’90s was making simple, black-and-white photographs chronicling her Black domestic life. Weems didn’t take her first photo until she was 37; LeSeur thought it wasn’t too late for a career change.

When LeSeur enrolled in a darkroom photography class, she began taking portraits of her Black college peers and fellow basketball teammates as a way to process the racism—being called the n-word, getting turned away from parties—they were subjected to at Bucknell. A few years after she graduated, the school made national headlines for students declaring on a college radio show that “Black people should be dead,” and to “lynch ’em.” “It was a rough four years,” LeSeur told me. After graduating, she continued studying photography at the Savannah College of Art and Design, around the time that Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown were killed. By then, she was taking photographs of natural landscapes that referenced the murders. But she felt something was missing. It wasn’t until she came upon a survey of artist Vito Acconci’s autobiographical performances that LeSeur became inspired to stage her own, with a friend to help her film. For the first time, her work felt real.

Five years later, her videos became more complex, their subject matter more pointed and laced with reference and rage. The Whitney Museum-acquired Maybe rainbows do exist at night (2019) opens with a closeup of LeSeur’s face as milk pours down it, then cuts to an old clip of Alice Coltrane joyously strumming a harp. Another monitor blinks on with a closeup of LeSeur’s upper torso, gyrating to Gil Scott-Heron’s “Comment #1.” Over rhythmic drumming he indicts the young white students who allied themselves with the anti-racist Rainbow Coalition in the ’60s, sensing that they were too privileged to really understand Black experience. “The irony of it all, of course, is when a pale-faced SDS [Students for a Democratic Society] motherfucker dares look hurt when I tell him to go find his own revolution.” LeSeur’s collar bones twist hypnotically. The piece flits through moods and genres of music—the melodies of saxophonist Archie Shepp give way to the Sun Ra Quartet’s ethereal, bluesy “When There is No Sun”—before all goes silent and we see LeSeur’s face one more time in close-up, bathed in blue. She looks at us unblinkingly, otherworldly, then hangs her head limp before suddenly pulling it back and letting out a mute, protracted scream. Or maybe it’s a sob. If we could hear it, it would no doubt be blood-curdling.

Police brutality features prominently in There are other hues of blue (2019-2021). Five flat-screen television monitors hang in a cluster and ethereally emit changing shades of the namesake color, which are derived from a Facebook Live video filmed by 21-year-old Dreasjon Reed when he was shot by cops. His phone falls to the ground and the camera faces the sky, scattering the sun’s light into shades of blue. “I’ve been present,” she narrates, “in a body that’s been shot at, spit at, cursed at; tied down, hung, set aflame, whipped. But she asked me again. Is your spirit awake?” As LeSeur speaks, the monitors rotate through aqua and ultramarine as fleetingly as clouds move over the sun. The effect is emotionally devastating, and characteristically LeSeur. “Le's practice is special, like her,” Vivian Chui, the curator of LeSeur’s “Monument Eternal” exhibition told me over email, “because it transforms dark historical narratives into incredibly moving meditations, without being prescriptive.” There are other hues of blue, like all of her work, is also about trying to heal. “There is so much violence in the world,” LeSeur said about the piece. “We have to think about what happens after. Where are the small moments of tenderness and care? How beautiful it is to be alive and carry out that potential for someone else who, tragically, can’t do it anymore.”

*

A few weeks following the opening of “Monument Eternal,” LeSeur and I walked through the exhibition together, looking at the completed works—framed, hung, and looped—that we had discussed, in-process, just months before. The namesake video ran on one wall, and the rubbed drawings using charcoal, Stone Mountain Daisies, and hibiscus were positioned on another. A stained glass wall evoked her days as a child going to church, which was a communal meeting place for extended family and friends. Nearby, a glass sculpture sat on a pedestal, its shape inspired by her breath on the mountain; breathing in and out into the hot glass, she had created a lung-like form on the brink of collapse.

We grabbed a drink at a bar around the corner from Pioneer Works after, and, as usual, our conversation turned to Stone Mountain. “It's weird being so fascinated with this place,” she told me. “I’m always wondering if I’m going too far with it. What is it about Stone Mountain that keeps bringing me back?” Now that the show was done, LeSeur could, in theory, move on. But she wants to expand Monument Eternal into multiple channels that incorporate archival footage of the site, as well as material from other places with fraught histories of race and violence, like Tulsa, where she’s midway through a three-year fellowship. Stone Mountain felt like an unresolved thorn in her side, I mused as we sipped our beers, and suggested that maybe the ambivalence of others towards its complexity was, itself, the thorn.

She nodded, and told me she would be returning in a few weeks, when her mother would be recovering from hip surgery. When I told her I had recently returned there myself, on my own, she suggested maybe both of us were a little weird and laughed, her smile radiant and warm. ”I have a very intense sensitivity to the land,” she said.

When I went back in early October, I had no real agenda aside from hiking the Cherokee Trail—named after the local tribe indigenous to the area—on the advice of a Black Uber driver I’d chatted with who had turned out to be a Stone Mountain fanboy. The visitor center was surprisingly quiet, even for a weekday. A park map indicated the path passed a small, crystalline lake at the mountain’s base, which I discovered was so still that it captured a mirror image of the galloping generals hundreds of feet above. Tucked into adjacent woods was a dated memorial I’d never seen before, a time capsule from when the park had been officially opened to the public in 1965, on the centennial of Lincoln’s assassination. There was a bronze statue of a shirtless man holding a broken sword, and a plaque dedicated to a Confederate soldier shortly before his death. Behind it, the mountain’s streaks of erosion from years of falling water rose high above the trees. Bathed in the sacred glow of the fiery cross.

I walked deeper into the forest, following the banks of a burbling stream. I imagined LeSeur also wandering this path. What exactly were we searching for? Hemmed in by ferns, the trail cut through stands of pine and oak trees. As I walked, everything became hushed and still, as the sound of vehicular traffic gave way to birds and fluttering leaves. Above me, light filtered through a glistening tree canopy. It was beautiful, and I realized I was all alone. I continued walking through a dense understory, discovering a small DIY spur, which I followed up to a birch tree before hooking right. Rounding the corner, I gasped. Not 15 feet from my face was a nearly vertical wall of granite. I had stumbled, literally, into the mountain, which looked like it had landed, alien, from another time and place. Do you know this place? Since your breath is no longer here?

Craning my neck up, the rock seemed to stretch infinitely into the sky. On either side of me, massive trees had toppled over each other, pushed against the unyielding stone. I slowly approached and put my hands on it. It was smooth and dry. Turning around, I laid my back against the mountain’s side, rubbing my fingers against it. I looked up at the sky. Hawks flew high in the air, circling each other. Everything was quiet, as if time had slowed to geologic speed. I took in a breath and closed my eyes. ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast